Gema works at the Department of Social and Myrmecophilous Insects in Warsaw, Poland, Her current research article concerning task syndrome in ant workers and the connection between behavioral traits and task allocation can be found here.

IS: Who are you, and what do you do?

Gema: I am an assistant professor at the Department of social and myrmecophilous insects from the Museum and Institute of Zoology (Polish Academy of Sciences). I work with ants, and my main research topic is focused on the impact of anthropogenic changes in the habitat on the ant communities and functional traits. Since my PhD studies (at the University of Cordoba, Spain), I have been very interested in the impact of urbanization on ants; so I made it my main research topic. Besides, I am involved in forests research (mainly red wood ants) and other topics including behaviour, vibroacoustics and, more recently, the interaction between the entomopathogenic fungus Rickia wasmannii and Myrmica sp. Also, I am passionate about ant taxonomy and, although it is not my research topic, it has been a very important tool in all my studies, and it has also helped me to collaborate in diverse projects.

Gema and her dog Rila

IS: How did you develop an interest in your research?

Gema: It was during my PhD when I started to learn about urbanization and its impact on ants. I realised that, although it is not a very novel topic, there is still a lot to learn about; so, I kept learning, questioning and searching for answers. Although there were many things to investigate, there is something clear in this topic: Urbanization is an unstoppable phenomenon that is causing drastic changes at all levels. But I also found that similar trends and stress factors can be found in all other anthropized habitats, and that’s the key! We live in a stressed world, causing climate change, habitat loss, biodiversity loss, pollution… and I would really like to contribute to improve the situation. Thus, I believe that a better understanding of the impact of urbanization can strongly help to find (or at least get closer) to a solution for this environmental crisis. I have so many questions that I would really like to answer…

IS: What is your favorite social insect, and why?

Gema: Ants, no doubt. I think that they are amazing in all aspects. Doesn’t matter if you check their taxonomical diversity, their social organization, their impressive capacity for learning or their behavioural and physiological adaptations… We are always fascinated to see how big mammals (e.g. primates) and humans share some traits (like the tool use), but these traits are generally unnoticed when it comes to small animals like ants. It is simply impressive how much you can learn from such a small organism. Besides, ants are addictive! The more you learn about them, the more you want to keep learning.

IS: What is the best moment/discovery in your research so far? What made it so memorable?

Gema: It’s not an easy question but I really like this one: A few years ago, it was cold and dark when I was arriving home in Warsaw. In my neighbourhood, the heating system of the buildings are coming from a common boiler and the heat is distributed through pipes. Behind my parking spot, there is a sewer drain cover that keeps warm because of the heating system. So, although it was cold, some ants from a Lasius niger nest near the sewer were active whereas the other nests far from the warm spot were inactive. So, I started to think about the urban warming, and I started to apply for grants to study the urban heat island effect. This initial observation has already resulted in two successful grant applications, enabling me to conduct a comprehensive, large-scale study that involves international collaborations.

IS: Do you teach or do outreach/science communication? How do you incorporate your research into these areas?

Gema: Unfortunately, I rarely do it. I work in a research institute, so lectures are limited to the doctoral school or if you are invited in a university, an event… Although it is very rare that we are invited, sometimes it happens. Then, I usually like to give some general information about ants. After introducing ants, I like to show something about the research that we are carrying out in our laboratory, the purpose of these studies, how they contribute to advances in science and how we can use this information, for example, for species protection and habitat conservation. I have the impression that many people perceive science as something distant or disconnected from their daily lives. It is crucial for them to understand that our research has practical applications and direct effects on society. For instance, conservation ecology seeks to create a thriving environment that significantly enhances both the overall health of the ecosystem and the quality of life for humans.

IS: What do you think are some of the important current questions in social insect research, and what’s essential for future research?

Gema: It is actually a difficult question…I have realised that the most important questions in research vary among countries, scientific societies or even research groups. However, I personally think that there is not a specific important question because, from my point of view, everything is interconnected and each research is a piece of the big puzzle of nature. But if I must choose one, then I will come back to my topic: the impact of anthropization. We still don’t know how it really works in terms of species adaptations, long term impact, the indirect impact of interspecific interactions, etc… I think that it is essential for future research because without understanding what is happening, we can’t find a solution. And, well, we need a solution. Either if you like the topic or not, we all need a solution for the current environmental crisis if we want to enjoy a good quality and healthy life (for us or for future generations).

IS: What research questions generate the biggest debate in social insect research at the moment?

Gema: I have no idea. I think that there is a big debate in each research, so I will talk about my main topic. I think that the biggest debate relies on how species will get to survive: adaptation or phenotypic plasticity? However, I would also like to assess the indirect impact through the network of interactions among species, among many other things… Uff, I have so many questions that I would really like to answer…

IS: What is the last book you read? Would you recommend it? Why or why not?

Gema: I like to read books of different topics, I have not a favourite style. Right now, I am reading a book from 1973, “Protection of Man’s natural environment” (initiated by Prof. Władysław Szafer and prepared for publication by Włodzimierz Michajłow), but I just started. So, I will talk about a book that I enjoyed a lot “Sabias: La cara occulta de la ciencia”, a book written by Adela Muñoz Páez. My husband bought this book for me after listening to a talk that she gave at his working place. She is a scientist, so she has firsthand knowledge of the challenges faced by both the scientific community and women within it. As you read the book, you journey through the centuries, learning about the roles of women in different civilizations and in the field of science, beginning with Enheduanna (2300-2225 BCE). The book is incredibly engaging and full of intriguing information. It is written in a catching and comfortable way. So, I definitely recommend it. The only issue, I think that it is only available in Spanish.

IS: Outside of science, what are your favorite activities, hobbies, or sports?

Gema: My favourite and more personal healing activity is to have a walk in the field with my dog (if my husband joins us, even better). I love dogs, both to teach them and learn from them is a wonderful experience. Travelling, that’s something that I also love and my long term plan with my husband would be to visit as many different countries as possible (the whole world would be perfect, although it isprobably a not too realistic plan). Although I can’t do it as much as I would like to, I enjoy practising some water sports (like swimming or windsurfing) and in recent years have practised some martial arts. I am quite a beginner in these sports, but I really enjoy them and they help me to disconnect from work.

IS: How do you keep going when things get tough?

Gema: Very good question… I really don’t have an answer for that. Sometimes it becomes really hard. Research is a very beautiful work, but also hard and the system needs some changes. Unfortunately, this is not just my reality, but the reality of many researchers. So basically, I think that you just keep going, trying your best and keeping the hope that maybe in the future the situation will improve. And, of course, it really helps that there is always some researcher willing to help you and support your research. But, undoubtedly, the support of your family and your friends is essential to overcome hard times in science.

IS: If you were to go live on an uninhabited island and could only bring three things, what would you bring? Why?

Gema: Very simple answer, but I would like to bring my family pack including my husband and my dog. So, 1- my husband and my dog; I think that we finally deserve to enjoy a long time together and being with them makes me happy. 2 – a tool kit (with knives, pliers, hammer…); obviously, I will need to build something where to live and get food; 3 – a fully equipped stereo microscope; probably there will be not too many ants ion n an island, but it might happen that some species might have arrived somehow… I don’t want to miss anything.

IS: Who do you think has had the most considerable influence on your science career?

Gema: Well, many people played a part, but if I must choose then I will choose two persons: Prof. Joaquín L. Reyes López and Prof. Wojciech Czechowski. I have my PhD thanks to Prof. Reyes López. He is the one who infected me with the passion for ants, and the one who supported me when nobody thought that I could get a PhD. My career has been a bit different because I didn’t jump into the PhD after I finished Biology, instead I tried different jobs before I decided that what I really wanted to do was science. But not too many people are willing to support a person without a grant and whose only option is to do a PhD while working full time in a company. But Joaquin was there, he decided to be my supervisor and teach me at lunch time, weekends… still now I keep learning from him. After that, Prof. Czechowski helped me. I arrived to Poland for personal reasons and I decided to contact with his department. I was so lucky… because he is also a person who is always willing to help and so he gave me an opportunity… and here I am, still working in this department, learning from him and working together.

IS: What advice would you give to someone hoping to be a social insect researcher in the future?

Gema: Hard to say… It is really difficult to be a researcher nowadays. But if I have to give some advice, then I would definitely advice to choose a good and productive laboratory with funds for research. It will lead you to have a good number of high-quality publications, which will open many doors. Unfortunately, working hard is not enough… Doing the complete research and publishing in a good journal is costly, and not every lab can afford it. Also, a good lab will facilitate you a valuable research network. But it is also important to consider whether you fit in that lab. After all, you will have to spend almost 70% of your life with these people during the few next years. If you don´t fit, it will be really hard to keep going.

IS: Has learning from a mistake ever led you to success?

Gema: well, I think that this is a very common situation. I don´t know how many times I made a mistake, but for sure I did it many times. The thing is that you always learn something from these mistakes, sometimes for good (you get something worthy and new) and sometimes for bad (you learn that it is better not to do it again).

IS: What is your favorite place science has taken you?

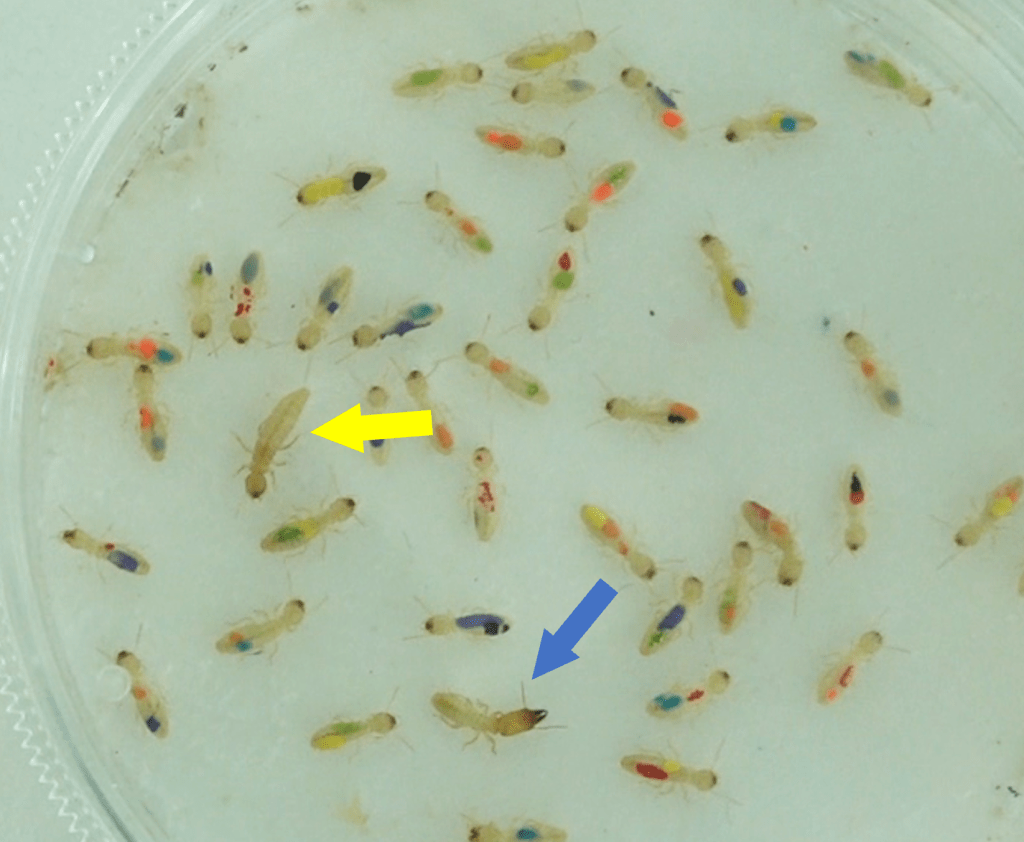

Gema: It wasn´t directly science, but I went there with my salary working on science. I went to Sri Lanka and I fell in love with the country, the people, the landscapes… Sitting in the patio and see the flying foxes passing above you, having a walk in the village and see all sort of animals on the way, the amazing and numerous ant species, huge termite nests, the turtles, the leopards sitting in front of the car! Funny but shocking situations like a guy throwing a stick in a lake and see dozens of crocodiles moving there just to show us that the place was full of them (I thought that we would get back to the village without that guy…), Adam´s peak and little Adam´s peak, the people… There are no words to describe the experience.