Stefan Popp is a PhD student, soon to be a Doctor, working on the foraging behavior of ants. His recent research published in Insectes Sociaux can be viewed here.

IS: Who are you, and what do you do?

SP: I am Stefan Popp, and I am interested in invertebrate behavior. In my PhD with Anna Dornhaus at the University of Arizona, which I just finished this August, I investigated the search behavior of ants. In my thesis, I described a regular meandering pattern, which makes the ants’ search more efficient. I also found that colonies in a new environment explore the vicinity of their nest more on the first day, and that interindividual search behavior variation might be more important for colony coordination than communication via chemical footprints.

IS: How did you develop an interest in your research?

SP: From very early on I have been interested in the critters in my backyard and have devoured every nature and science documentary on TV, to the point where my first dream job I can remember was ‘nature documentary film maker in the Amazonas basin’. The two topics I would get most excited by were animal cognition and swarm behavior. During my bachelor’s at the University of Würzburg I did several internships to check whether I really wanted to study ants and have stuck with it ever since.

IS: What is your favorite social insect, and why?

SP: I adore all highly visual and aggressive ants, like Indian jumper ants (Harpegnathos spp.) or weaver ants (Oecophylla spp.). The way they look at you makes my heart melt more than any puppy or kitten could.

IS: What is the best moment/discovery in your research so far? What made it so memorable?

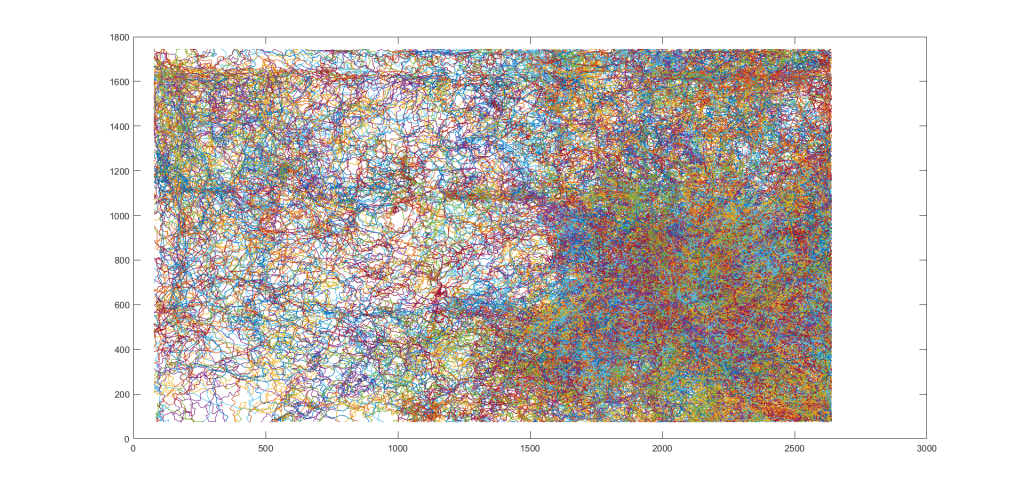

SP: Seeing the first tracks from the tracking software from the early-2000s and spotting the regular turning patterns we describe in my first publication from my PhD. First, it felt like magic getting that tracking script to work with very little coding experience. Then, seeing that fractal-like pattern of ants meandering like rivers, which is invisible when you’re just watching the ants move in real time (they walk very slowly), made me think that this is the first real ‘discovery’ of my career. This was now 6 years ago, and I am still trying to answer questions about the ‘why’ and especially ‘how’ of this behavior.

IS: Do you teach or do outreach/science communication? How do you incorporate your research into these areas?

SP: I taught various courses throughout my PhD studies and often tried to give at least one brief lecture on cool ants and my research and use ant examples, adding a personal touch and more organic enthusiasm. I also somewhat regularly upload vlogs about my life as an international PhD student, presentations, and science communication videos to YouTube. In the beginning I did weekly vlogs, but that became a bit much after a couple of years. I also participated in outreach events at local schools and festivals, but to me, the day-to-day interactions with strangers are at least just as important. As an anecdote, I recently went to a conference in Tel Aviv. The day before the conference started, I participated in a walking tour of the city, where I got into a conversation with a young couple. They were so fascinated by what I do that after the tour, we sat down, I pulled my laptop out, and gave an impromptu presentation about my work and social insects in general. After 2 hours of intense science conversation, they invited me to a snack at the local market and we continued with our afternoons. That was a very gratifying experience.

IS: What do you think are some of the important current questions in social insect research, and what’s essential for future research?

SP: What do all the lesser-studied species do? Like many, I believe that we need a lot more natural history knowledge about a broad range of species. There are so many fascinating behaviors we have discovered, from face-identifying wasps over ball-playing bumble bees to wound-caring ants. With the vast diversity of lesser studied social insects there are bound to be many more behaviors of this kind waiting to be uncovered. I hope I can contribute to that knowledge myself in the future.

IS: What research questions generate the biggest debate in social insect research at the moment?

SP: To me, it is the whole division of labor, task allocation and specialization debate. As a spectator, it feels like everyone gets some bits right but doesn’t necessarily acknowledge the great complexity of it across species.

IS: What is the last book you read? Would you recommend it? Why or why not?

SP: In our last book club in the lab, we read ‘The Mind of a Bee’ by Lars Chittka, and I can recommend it. The author gives a nice overview of the sensory and cognitive abilities of bees and weaves in many anecdotes from his own research career and that of other scientists, some from more than 100 years ago. Despite having quite some knowledge on social insects I still learned a lot from it and generated lots of questions. The biggest weak point, in my opinion, is that the word ‘consciousness’ is never defined. As a bonus, I would like to give a podcast recommendation: The Huberman Lab. Andrew Huberman is a neuroscientist who gives extensive reviews in podcast form on the science of health, productivity, and well-being. I now know a lot more about the brain and could implement a lot of the tools and habits.

IS: Outside of science, what are your favorite activities, hobbies, or sports?

SP: I love snowboarding and trail running and sometimes go on multi-day bikepacking tours. I also enjoy going to EDM festivals (a.k.a. ‘raves’) and learning languages. I’m currently learning French with the Comprehensible Input method. And there is never enough time to learn about other fields of science through YouTube videos…

IS: How do you keep going when things get tough?

SP: I try to schedule enough exercise and being social, which are the foundations of my well-being. I typically don’t compromise on sleep, so don’t have to worry too much about that. I’m a huge fan of self-improvement, so in difficult periods I try to apply some of the practices from the many books and podcasts I consumed and reread certain books just to get me into the right mindset. What pushed me through tough times during my PhD studies was the knowledge (or faith) that all you need to be successful is grit. The rest will fall into place somehow.

IS: If you were to go live on an uninhabited island and could only bring three things, what would you bring? Why?

SP: Three friends (or whoever wants to come). The pandemic lockdowns showed me that human connection is invaluable.

IS: Who do you think has had the most considerable influence on your science career?

SP: My PhD advisor, Anna Dornhaus. She has strong opinions on how science should be done and was the best advisor I could imagine. I gained a lot of practical knowledge about how to navigate academia and she is always a cheerleader for her students. Anna was always very supportive, loving, and honest, which made my experience in the PhD and in academia in general very positive.

IS: What advice would you give to someone hoping to be a social insect researcher in the future?

SP: This goes for any field: Try to get an idea of what you really want to know and what you would like to do day-to-day. Observe social insects and bring your implicit questions to the forefront of your mind. Read broadly and follow rabbit holes. Do research internships whenever possible! Don’t be afraid to cold-email professors.

IS: Has learning from a mistake ever led you to success?

SP: I’m still waiting for the success resulting from many of my mistakes… Besides the usual improvements of writing, presentations, and coding through feedback, I often made the mistake of not introducing myself to professors at conferences just to make myself known. I learned from the regret and gained some opportunities from such encounters.

IS: What is your favorite place science has taken you?

SP: Cote d’Ivoire. I spent 6 weeks there for a project that could have become a part of my thesis but hasn’t worked out yet because of challenges tracking ants in the field. It was my first time in Africa and the closest I’ve been to the tropics. The people, nature, climate, and life at the field station all left very fond memories.