Oscar Vaes is a biologist interested in data analysis and scientific communication. He has just completed his PhD in Belgium. His latest work on “inactive” ants in colonies can be found here.

IS: Who are you, and what do you do?

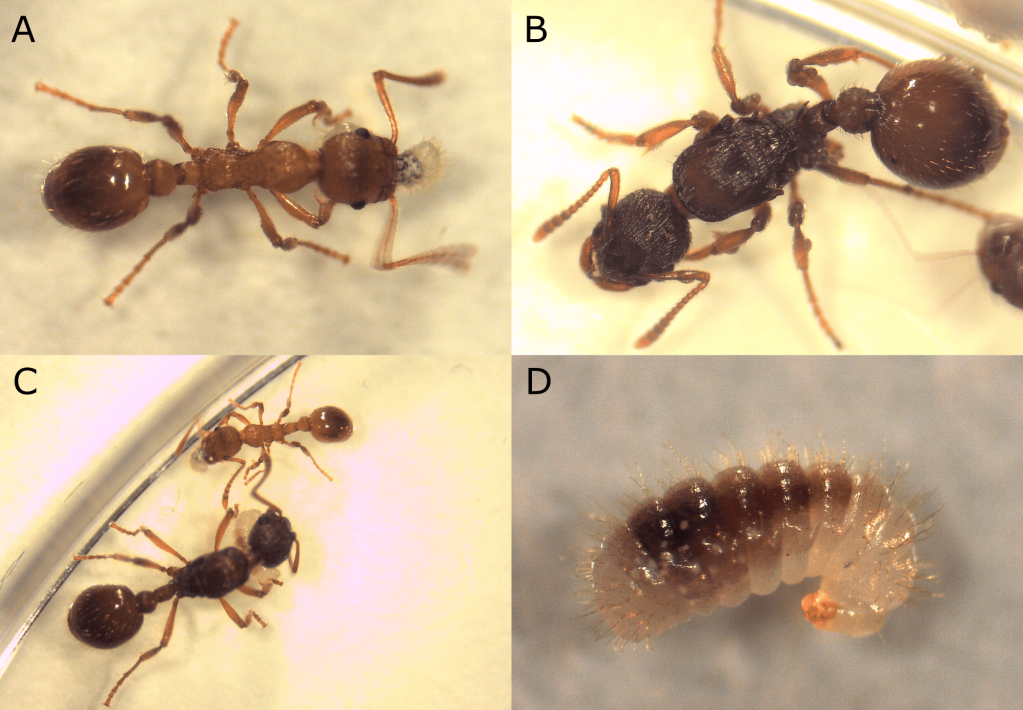

I’m a Belgian biologist and recently finished my PhD about activity levels in the red ant Myrmica rubra, at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. At present, I’m trying to put my knowledge of data analysis to good use, an aspect of research that I really enjoy and in which I’m trying to improve.

IS: How did you develop an interest in your research?

Simply by working on them. Basically, I’m curious to understand how things around me work, hence my interest in biology. This, combined with my attraction to animals, meant that I was predisposed to take an interest in social insects. However, it was really when I was looking for a research topic for my master thesis that I developed an interest in ants.

IS: What is your favorite social insect, and why?

So far, I’ve only worked on one biological model, Myrmica rubra, and although it doesn’t treat me in the best way during my experimental manipulations or field harvests, I still have to choose it. Being only at the beginning of my research career, I feel I’ve only glimpsed the tip of the iceberg, so I’m sure this favorite animal will evolve over time. Yet, I think it will always be a species of ant. I believe that they occupy a special place in the collective unconscious and fascinate people. I never tire of seeing the reaction people have when we tell them we’re studying the behavior of ant colonies. It is always a fun icebreaker.

IS: What is the best moment/discovery in your research so far? What made it so memorable?

My best moments are usually when I get to share with researchers from other laboratories, at conferences. These moments are always very enriching, and have the instant effect of taking us out of the tunnel vision we might have when working for months on our subject in an office.

In terms of discoveries, I based much of my PhD subject on the hypothesis that there was probably a large proportion of inactive individuals in colonies of the ant I worked with. Having confirmation that around 30% of our species’ colonies form a distinct group of nurses, foragers, and domestics, and that we could cross-reference their characteristics with those of other species, was one of those really exciting moments when the prospects for future experiments develop and become clearer.

IS: Do you teach or do outreach/science communication? How do you incorporate your research into these areas?

Passing on knowledge is something I really enjoy doing. I’ve always been attracted to teaching, without actually doing it professionally. As a result, I try to value the moments when I can explain my research and simplify it. I find that being able to explain complex phenomena in a simple way is a great asset, but it also reflects the fact that we ourselves have understood things in depth. So practicing simplifying/explaining research is also a way of assessing one’s own level of knowledge.

IS: What do you think are some of the important current questions in social insect research, and what is essential for future research?

There’s no particular research topic that stands out for me, and this is no doubt linked to the fact that I don’t yet have a global vision of the study of social insects. However, the development of computer tools has made it much easier to acquire certain types of data by automating their collection and processing in much greater quantities than was possible in the past. I think we need to keep a critical eye on the effect these tools have on the observer, his or her ability to interpret results or even spot phenomena. I have several examples in mind of times when I’ve spent weeks turning over data presented in spreadsheets in search of answers to questions we were asking ourselves, only to have the answer right under my nose all along on the videos of my colonies. Although computer tools are a great help most of the time, they tend to distort our vision of results. There’s nothing like the eye of the experimenter to give you a first-hand view of the phenomena you’re about to dissect!

IS: Outside of science, what are your favorite activities, hobbies, or sports?

I’d say bicycles are one of my main interests. Basically, it’s always been my means of transport in Brussels, but as I was working with it, I became interested in the mechanical side of things. This basically means I have several unfinished project bikes laying in a corner of my garage. Recently, I’ve been enjoying discovering the Belgian countryside by bike, and I have to say that it’s a fantastic tool for that. I also enjoy discovering new sports and eSports disciplines. I love the feeling of beginning to understand the reasoning behind the actions of professional athletes or players, of developing a form of expertise in a new discipline. Since it’s also more fun to share interests with others, I often get sucked into people’s passions.

IS: What is the last book you read? Would you recommend it? Why or why not?

It’s not related to my research topic, but the last book I read was written by Victoria Defraigne, and is an explanatory book on transidentity. Knowing it was written by a student at my university was the trigger to finally learn about a subject I knew was full of stereotypes and misinformation in my mind. I think that for the moment, this book only exists in French, but I urge people to get informed about a subject still full of misunderstandings.

IS: How do you keep going when things get tough?

To be honest, I think I’m lucky in that I never really have a hard time. I’m very privileged in life, with family and friends all around me, which makes it easy for me to put things into perspective when they don’t go as planned. So far, the difficult periods have all been relatively limited in time, with a clearer horizon in sight each time. So, I find it easier to accept the situation and tell myself that it’s only temporary, as all the previous tough times have been.

IS: If you were to go live on an uninhabited island and could only bring three things, what would you bring? Why?

I always have my pocket magnifier in my backpack, and I use it more often than you’d think. I’d have a hard time parting with it, so I’m going to choose this as my first item. I hope, of course, that by “uninhabited” we’re talking about humans and not local wildlife. In two, I’d say coffee beans, so as to quickly have a plantation to support myself. I wouldn’t accomplish much on a desert island without my morning coffees. As I have no idea about the third, I think I’d let friends choose for me, so I’d have a surprise on arrival, good or bad.

IS: Who do you think has had the most considerable influence on your science career?

I think my PhD promoter, Claire Detrain, takes first place hands down. Then I’d say it’s the rest of the team in her lab. When it came time for me to find a subject for my master thesis in the various laboratories at my university, I gave as much importance to the atmosphere and ambience within the team, as to the research subject. Today, I’m very happy to have followed my intuition, and as a bonus, I’ve taken an interest in our six-legged friends.

IS: What advice would you give to someone hoping to be a social insect researcher in the future?

Not to work on Myrmica rubra! On a more serious note, I don’t think there are any tips specific to the study of social insects. The only mistake I see being made frequently is that of systematically trying to draw parallels between our behavior and that of social insects, but it’s mainly made by a non-scientific audience. I imagine that anyone interested in social insects quickly realizes that a large part of their charm lies in the fact that their group is structured in such a way as to modify the implications that collective responses have on individuals and the group. Over the last few years, I’ve supervised a number of students who have all shown themselves to be very curious and eager for results when working on ants, without having any prior interest in these insects. So, I think we’re lucky to be working with animals that naturally arouse people’s interest and curiosity, which can only be a good thing.

IS: Has learning from a mistake ever led you to success?

Of course it did. One example I really like is when we first started doing individual marking of ants, and we were looking for the best way to do it. We struggled quite a bit with methods we used to perform in our lab, and finally decided to reach out to another researcher who seemed to have great results with a different technique, but whom we had never spoken to. Not only was he willing to give us a detailed explanation of his techniques, but we were able to implement many tips that completely changed our way of tagging. We have been training young researchers to tag ants with great success and will probably be using these tips for many years to come.

In a broader sense, I think that making mistakes reinforces our ability to question ourselves, something that is key when doing science. I find that conducting research helps us accept mistakes and learn from them. Moreover, I believe this translates into being more open-minded in life, deconstructing deep-rooted misconceptions, and being more apt to listen to others.

IS: What is your favorite place science has taken you?

I have a very ‘first degree’ answer to this question. I mentioned earlier my fondness for conferences, and I was lucky enough to attend IUSSI San Diego in 2022. So, I’d say it was one of the highlights of my thesis, where I was able to meet many people whose research inspired me, but also to discover the research subjects of laboratories from all over the world. I really enjoyed communicating my results to an international audience of social insect experts, whose feedback inevitably led to enriching and constructive discussions.