In this blog post, the authors of the Insectes Sociaux article title “High environmental temperatures put nest excavation by ants on fast forward: they dig the same nests, faster” (Rathery et al. 2025) talk about their research on the effects of environmental temperature on ant digging activity.

Imagine watching a video of someone doing normal everyday activities. First, at normal speed, then, at double speed: suddenly everyone moves like olympic sprinters, but still appear calm and relaxed. Now slow down the video: every step and gesture becomes painfully sluggish.

Imagine if that could also happen in real life: one day, it’s only noon and you have already wrapped up all the work for the day; the next day, you have barely had breakfast and the day is already getting to an end!

These situations look unrealistic to us, but ants experience them all the time!

Ants are ectotherms – animals that don’t maintain a constant body temperature. As a result, their physiology and behaviour depends heavily on the temperature of the environment. In warmer weather, ants move faster, they likely forage more quickly, and probably they also age faster. In our study, for instance, the walking speed of Lasius flavus ants doubled when the temperature rose by about 12 °C.

Of course, the sped-up video analogy only goes so far. For example, gravity does not change with temperature, so winged ants need to flap their wings at least at a minimum speed in order to fly, and this might become completely impossible in cold weather. At high-temperature, when ants are moving too fast, they might struggle to take in enough oxygen to keep up with their energy consumption. So, while some behaviours might simply speed up with increasing temperature, other behaviours are likely to hit a physical or physiological limit, and could change in unexpected ways. In all cases, the changes of behaviour induced by temperature are likely to be important for colony survival, and may play a role in future adaptations of ants to the changing climate.

IS: How did you choose this research topic, and to explore it with Lasius flavus?

“It was a combination of love for the topic, but also of practical circumstances”, says Alann Rathery, lead author of the study. Originally planning to study termite nests in Australia, his plans were upended by the Covid-19 pandemic. “I had to pivot quickly, soon abandoned the idea of travelling to Australia I began collecting ants from my backyard in London. At some point, I even ran some preliminary experiments in my room!“

“Luckily, the yellow meadow ants (Lasius flavus), which are one of the most abundant ant species in the meadows of South-West London, are very interesting ants. They are important ecological engineers, that shape the local landscape with their mounds, creating ecological niches for many other plant and animal species.”

IS: Can you tell us a bit about the experiments that you did?

“We have long been curious about how environmental factors – like temperature and humidity – affect the behaviour of social insects” – says Andrea Perna, senior author of the study. – “These environmental cues may help ants and termites figure out things that they cannot measure directly, like how deep inside the nest they are. One of the key functions of nests is to provide the colony with a suitable environment in terms of temperature and humidity: it makes sense that insects respond to these cues. In a related study (Facchini et al. 2024), for instance we found that termites may use water evaporating from damp soil as a signal to coordinate how and where to build their nests.

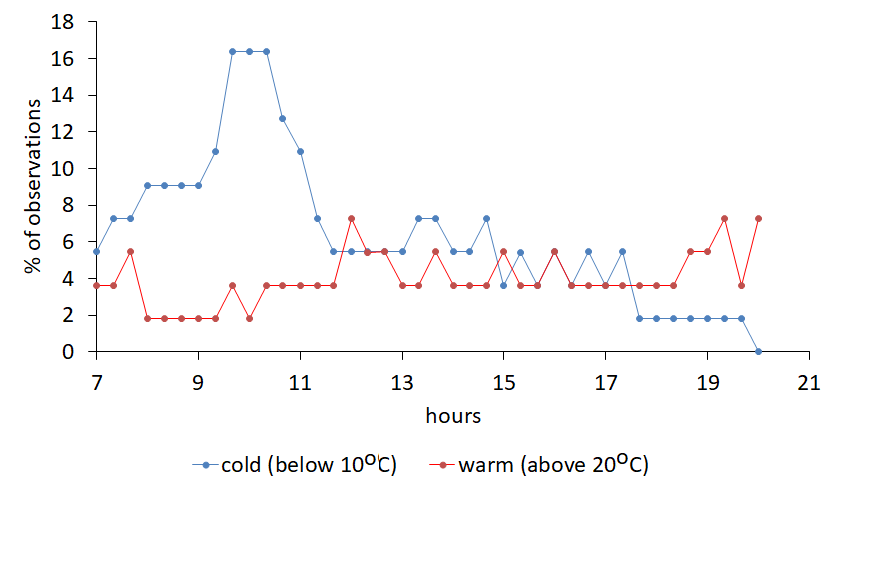

When it comes to ants, previous studies had indicated that they likely respond to temperature gradients – differences in temperature across space – during nest building. But it wasn’t clear whether temperature alone, without a gradient, could influence how ants dig or build. So we set out to test two things: first, how ant digging speed changes depending on temperature, and second, whether the shape of the nests that they excavated was different at different temperatures.

We followed a somewhat classical approach for the experiments, letting ants excavate in-between two glass plates, so that we could image the growth of the pattern over time while the experimental colonies were housed inside temperature-controlled incubators”.

“The experiments were technically a bit challenging – adds Alann Rathery – we had to image ant colonies continuously over multiple days, and the space inside the incubators was a bit tight, so I had to build a custom imaging system with Raspberry Pi computers and cameras – one inside each incubator. I connected them all to a router outside, and through that I could control the cameras remotely to automatically record photos and videos.” Analyzing the footage wasn’t simple either. “The ant tunnels grow into very complex shapes, and it takes a solid analysis pipeline to automatically extract and quantify the structures. But some of the patterns they create are really beautiful!”

Do you want to see these structures grow? Here is a time-lapse video of the growing galleries.

IS: What’s next for this type of research?

“There’s still a lot we don’t know about what happens at the individual level when ants dig these intricate underground networks. In our study, we didn’t focus on the detailed behavior of individual ants as they carve out tunnels in the soil. But what they do, how they decide where to dig, how new branches start, are all incredibly interesting questions. Some of this behavior can be seen in action in a real-time video clip from our experiments. Analysing in detail this type of footage is fascinating, but could easily become an heavy research task.

Another promising direction for this research would be looking at the internal structure of natural nests in the wild: how do galleries inside the mound differ, depending if the mound was built in a sunlit area compared to a shady one?Are there shape differences between the northern exposed and the southern side of the mound?

The nests built by social insects are more than just shelters: they are the physical records of the life and activity of a colony. If we learn to better read the information written in these structures, we might uncover new insights into the hidden lives of these wonderful insects”.

References:

Rathery, A., Facchini, G., Halsey, L.G., Perna, A. High environmental temperatures put nest excavation by ants on fast forward: they dig the same nests, faster. Insect. Soc. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-025-01049-7

Facchini, G., Rathery, A., Douady, S., Sillam-Dussès, D., Perna, A. (2024). Substrate evaporation drives collective construction in termites. Elife, 12, RP86843. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.86843.4