By Igor Eloi

Igor is a PhD student based at the UFRN campus on the brazilian coast. He is fascinated by how social insects, like termites, behave and interact with other species. In this blog, he shares key insights from a research paper exploring how fragment edges affect termite guests. His lastest research in Insectes Sociaux can be read here.

A termite nest is more than a mound of earth and wood; it’s a bustling city, a climate-controlled fortress engineered and built by tiny insects. These complex structures are not just homes for termites, a rather exquisite diversity of organisms have evolved to life within their walls.

There residents are known as”termitophiles”—organisms that live their entire lives, or at least critical parts of them, in an obligatory relationship with termite society. They are not merely guests but are deeply integrated into the colony’s day-to-day routine. These creatures have evolved alongside their hosts for millennia, developing bizarre forms and behaviors to survive and thrive inside the fortress. Which raises a rather pertinent question: If a creature is perfectly adapted to live inside a protective, self-regulating termite nest, does that make it immune to changes in the outside world? In other words, what happens to these hidden, highly specialized residents when human activity, like a simple dirt road, encroaches on their world? Our study set out to find the answer, revealing just how far the ripples of habitat disturbance can travel.

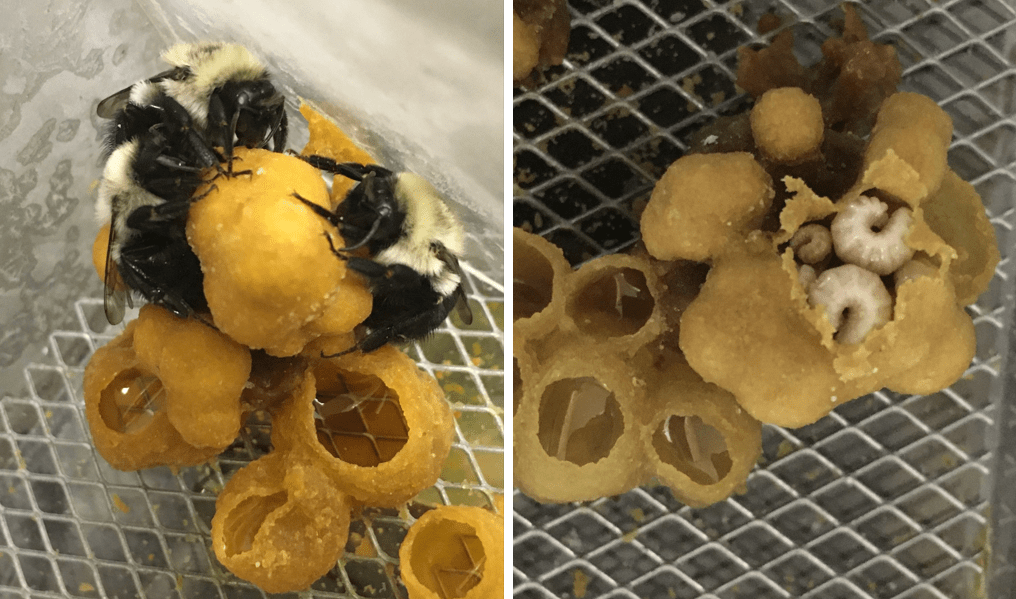

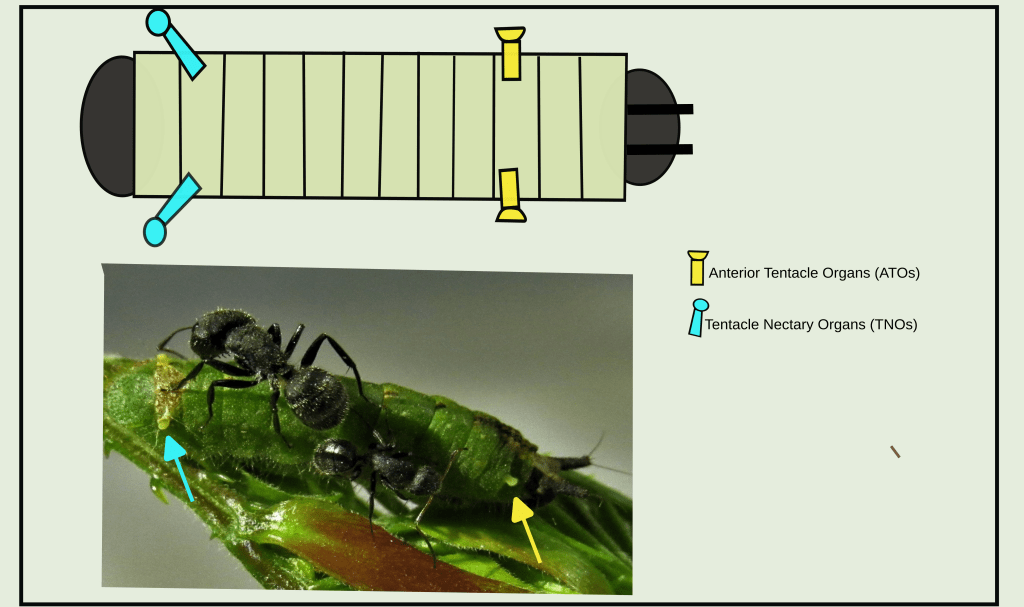

We focused on studying two Aleocharinae beetles, that live in an asymmetric “obligatory relationship” with a their host. This means that while termites live fine without the beetles, the beetles themselves cannot survive without the colony. We examined two distinct types found in the arboreal nests of the termite Constrictotermes cyphergaster (Nasutitermitinae).

On the image below, the first, Termitocola silvestrii, is a miniature tank. This species is equipped with a “limuloid” or drop-shaped body, featuring a large, shield-like pronotum thought to be a defensive adaptation against termite attacks. Anecdotal observations suggest it may act as part of the colony’s cleanup crew, feeding on dead termites. While these beetles possess wings, researchers speculate they may lose the ability to fly after successfully settling within a host colony. This secret society has its rules, and both species rely on momentarily leaving the nest—either for reproduction or dispersal—exposing their hidden world to the conditions of the wider forest.

The second, Corotoca fontesi, has a bizarre “physogastric” body, with a swollen, soft abdomen that gives it a strange, almost larval appearance and reduces its mobility. Its life cycle is a drama of dependence and risk. To reproduce, the female must venture outside the nest during the termites’ open-air foraging expeditions (Moreira et al. 2019). She then deposits a single, motile larva into the ground litter. The larva develops alone in the soil, and how it later finds and integrates into a new host nest remains one of the fascinating mysteries of its life cycle.

The central finding of our study is that despite living inside the protective, climate-controlled environment of a termite nest, the abundance of these specialized beetles is negatively impacted by proximity to a forest edge. This finding demonstrates that the so-called “edge effect”—the ecological changes that occur where two habitats meet—penetrates the defenses of the termite fortress.

One might assume that the nest would act as a perfect buffer against external environmental stressors. However, the study’s results suggest otherwise, highlighting that even for organisms living deep within a host structure, the human-made landscape changes of the outside world matters immensely.

Finally, it is our thought that the mechanisms behind the impact of edge effect over the abundance of termitophiles might lie in one (or the combination) of these:

- Direct Impact: The harsher environmental conditions at the forest edge—such as different temperatures or humidity—could directly harm the beetles during the parts of their life cycle spent outside the nest. For example, the larvae of Corotoca developing in the soil could be exposed to increased predation or unsuitable microclimates (Zilberman et al. 2019).

- Host-Mediated Impact: The termite colonies themselves might be stressed by the edge conditions. This could make them “lower-quality hosts,” perhaps with fewer resources or a smaller workforce, rendering them unable to support large populations of their beetle symbionts.

- Dispersal Limitation: The altered landscape near the road could act as a barrier. This might make it more difficult for adult beetles to travel between nests, limiting their ability to find and colonize nests located near the forest edge.

References:

Moreira IE, Pires-Silva CM, Ribeiro KG, et al (2019) Run to the nest: A parody on the Iron Maiden song by Corotoca spp.(Coleoptera, Staphylinidae). Papéis Avulsos De Zoologia 59:e20195918–e20195918.

Siqueira-Rocha, L., Eloi, I., A Luna-Filho, V. et al. Aleocharinae termitophiles are affected by habitat fragmentation in deciduous dry forests. Insect. Soc. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-025-01076-4

Zilberman B, Pires-Silva CM, Moreira IE, et al (2019) State of knowledge of viviparity in Staphylinidae and the evolutionary significance of this phenomenon in Corotoca Schiødte, 1853. Papéis Avulsos De Zoologia 59:e20195919–e20195919. https://doi.org/10/gng3q8