By Amalia Ceballos-González

In this blog, Amalia from the University of São Paulo tells the story of how she and her colleagues studied a strange functional behaviour in a myrmecophilous riodinid caterpillar. Read her latest article in Insectes Sociaux here.

Caterpillars that establish close interactions with ants have developed various adaptations to maintain the ants’ attention. These adaptations involves specialized organs that produce nutritional rewards or chemical signals to attract ants. The butterfly families Lycaenidae and Riodinidae provide many examples of myrmecophilous caterpillars, including species with these organs. In our recent study, published in Insectes Sociaux, we explored the impact of these specialized organs on ants by focusing on a species from the less-studied family Riodinidae, Synargis calyce, which interacts with various ant species. In our study area, the most frequent interaction involved the ant species Camponotus crassus.

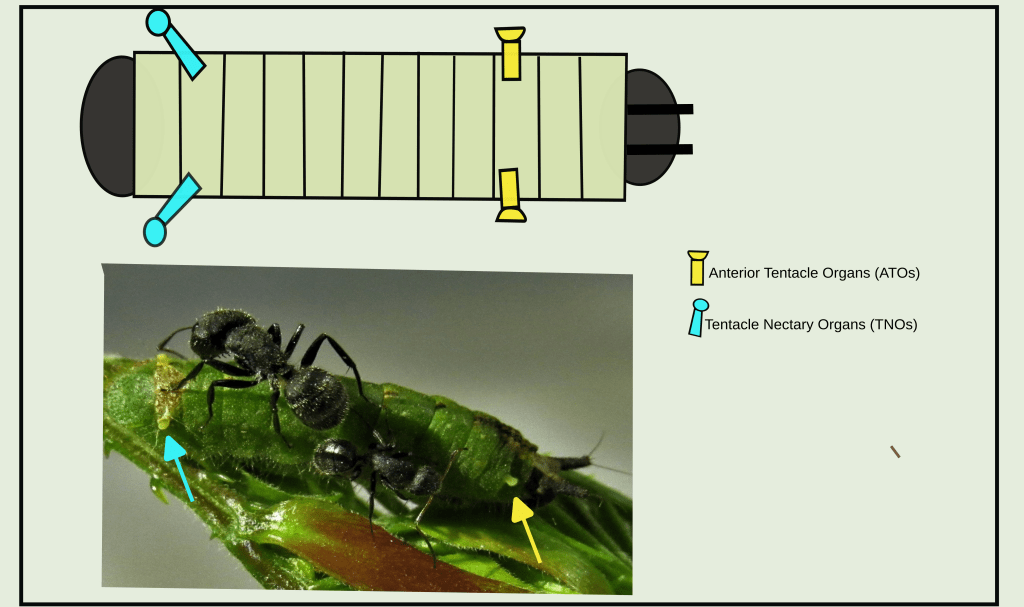

Caterpillars of this species possess two pairs of tentacular organs. The first pair, known as ATOs (Anterior Tentacle Organs), likely release volatiles that influence ant behavior, although there is insufficient evidence to confirm this. The second pair, known as TNOs (Tentacle Nectary Organs), secrete a nutritive substance (primarily composed by sugars and amino acids) that ants consume. Whether these organs work synergically or if one is more relevant than the other was still unclear for our study species and it is also the case for many other species of the family Riodinidae.

To uncover those aspects, we aimed to explore this pair of tentacular organs by checking ants’ reaction. Our research was conducted at the University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto campus. Our first objective was to create an ethogram documenting the behavioral interactions between caterpillars and ants. During these observations, we identified a striking behavior. The ethogram revealed that after the eversion of ATOs, ants exhibited stereotyped “jumping” behavior. This behavior involved ants rapidly lifting their legs and jumping towards the caterpillar’s head.

Next, we conducted experiments in which we experimentally manipulated – by allowing or preventing them to evert – the two types of caterpillar organs (TNOs and ATOs), to determine their role in maintaining ant attendance. Our findings demonstrated that TNOs are more effective in maintaining the attention of attendant ants, likely due to the rewards these organs provide. However, we also found that caterpillars with only functional ATOs received more attention compared to those with neither organ functioning. This indicates that TNOs play a central role in sustaining ant-caterpillar interactions, while ATOs serve a complementary function.

In conclusion, the interactions between S. calyce caterpillars and attendant ants are primarily driven by the rewards produced by TNOs, with ATOs playing a smaller, supportive role. These findings are consistent with observations in Lycaenidae species, which exhibit similar mutually beneficial relationships with ants. The evolution of these organs may represent a case of convergent adaptation to environmental pressures experienced by caterpillars in both families.