By Leeah Richardson

Leeah is a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin with a particular interest in insect behavior and anthropogenic stressors. In this blog, she explains how, although not highly lethal to adults, some pesticides can harm bumblebees in indirect ways. Her latest research in Insectes Sociaux can be read here.

Worldwide we use billions of pounds of pesticides each year agriculturally to control crop pests (FAO 2024) but this negatively impacts many insects that benefit crop production – for example: pollinators. Regulatory agencies do try to minimize the impact pesticides have on pollinators, but this is largely by preventing lethal effects. Pesticides don’t always have to kill bees to harm their populations and the pollination services they provide. By asking how much of a chemical is lethal to adults, we can miss subtle yet important effects on bee behavior and reproduction.

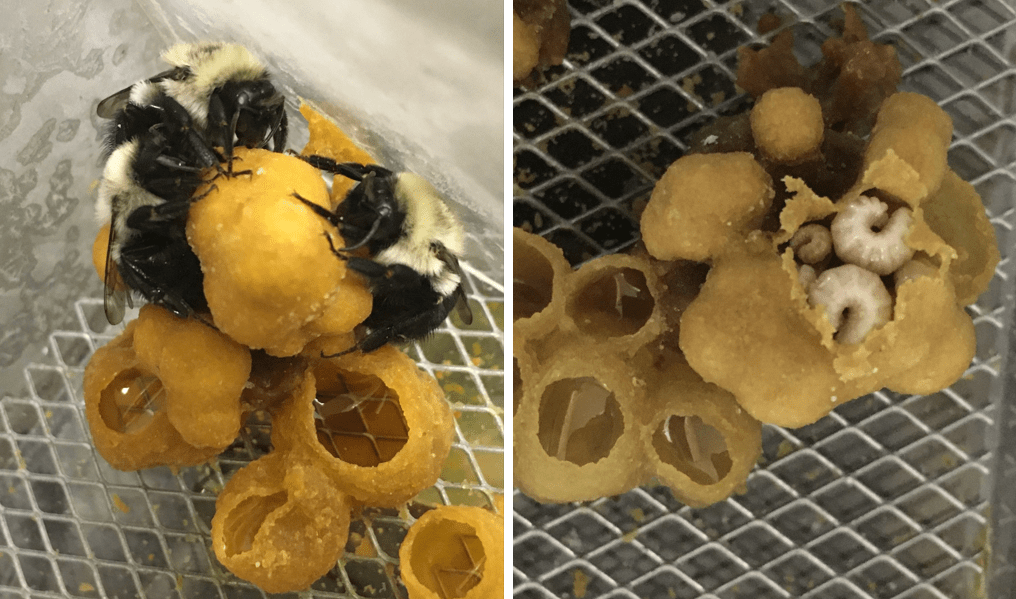

For many animals, including most bee species, offspring receive care from adults in order to survive. For example, in a bumblebee colony, worker bees chew through the wax covering their larval sisters to feed them pollen and nectar, regulate the temperature of the colony, and perform hygienic behaviors, so that these larvae can develop into adult bees. These caretaking behaviors are critical, but can be vulnerable to environmental stressors, like exposure to insecticides.

The insecticide Flupyradifurone (FPF) is especially interesting to study in the context of how it may influence bee caretaking behaviors FPF is not likely to outright kill adult honeybees or bumblebees at the concentrations present agriculturally – so it can be sprayed on flowering crops, but recent studies have shown that it has negative effects on bumblebee larvae (Fischer et al. 2023, Richardson et al. 2024). This raises the question: are bee larvae themselves sensitive to FPF, or is the problem that exposed adults provide poorer care to developing larvae?

We conducted two experiments to determine whether FPF is directly toxic to larvae through ingestion or if FPF has indirect effects by impairing caretaking behaviors (below).

We first did an experiment where we fed larvae by hand so that parental care was completely standardized for all of the larvae. To do this, we took larvae from an existing colony and kept each larva in an individual well of a 24-well plate, provisioning them with a sugar water/pollen mixture four times per day for three days. This mixture was either untreated (control) or contained FPF at one of four concentrations. If FPF was directly toxic, we expected to see higher mortality or delayed molting with the treated larvae. Instead, we found no differences between our untreated control groups and the treated larvae.

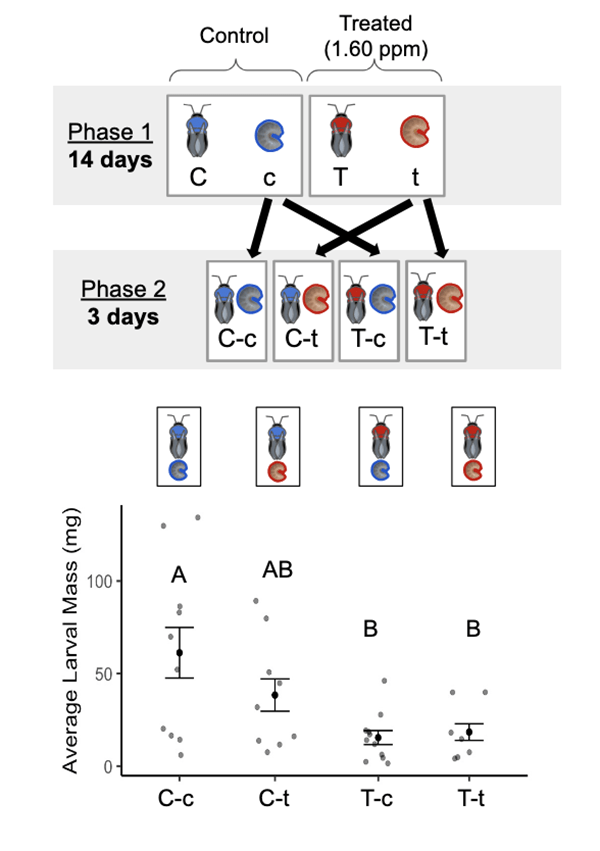

We then conducted a cross-fostering experiment to test for both direct and indirect effects to larvae. We created small “microcolonies” with four worker bees each that begin laying eggs and rearing offspring once separated from their queen. Half of these microcolonies were given FPF treated sugar water for two weeks, while the other half got untreated (control) sugar water.

After two weeks, we swapped the adults to new microcolonies so that we now had groups of larvae that had never been exposed to FPF being cared for by FPF-treated adults, and groups of larvae that had been exposed to FPF being cared for by untreated (control) adults for three days (see figure below). This design allowed us to see whether larval outcomes depended on what the larvae themselves had previously ingested or on the status of their caretakers.

We expected that if FPF directly impaired the larvae then whether or not the larvae themselves had been exposed to FPF for the two weeks prior to cross-fostering would strongly influence larval outcomes, but if indirect effects due to impaired parental care was most important then whether or not the adult caretakers had been exposed to FPF would instead be most influential. We found that it was the adult exposure to FPF that had the largest impact on larval outcomes (particularly the size of the larvae). Larvae tended by FPF-exposed adults were consistently smaller than those cared for by untreated adults, regardless of whether the larvae themselves had ingested FPF previously.

Both our hand-feeding and cross-fostering experiments showed that the larvae were surprisingly tolerant to direct FPF exposure via ingestion, but they were highly sensitive to impaired care. Together, these findings suggest that FPF’s harm to bumblebee larvae is driven mainly by changes in adult behavior, not by direct toxicity to the young.

Bee declines are complex, driven by habitat loss, climate change, disease, and pesticides (Goulson et al. 2015). Our study highlights the importance of testing not just whether pesticides kill adults, but also whether they disrupt the social and parental behaviors that larvae depend on. Future work should extend these kinds of experiments across more bee species and under field conditions, where multiple stressors interact.

References:

Fischer, L. R., Ramesh, D., & Weidenmüller, A. (2023). Sub-lethal but potentially devastating—The novel insecticide flupyradifurone impairs collective brood care in bumblebees. Science of The Total Environment, 903, 166097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166097

Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C., & Rotheray, E. L. (2015). Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science, 347(6229), 1255957. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255957

Pesticides use and trade. 1990–2022. (2024). Food and Agricultural Organiation of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/statistics/highlights-archive/highlights-detail/pesticides-use-and-trade-1990-2022/en

Richardson, L. I., DeVore, J., Siviter, H., Jha, S., & Muth, F. (2025). Bumblebees exposed to a novel ‘bee-safe’ insecticide have impaired alloparental care and reproductive output. Insectes Sociaux. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-025-01054-w

Richardson, L. I., Siviter, H., Jha, S., & Muth, F. (2024). Field‐realistic exposure to the novel insecticide flupyradifurone reduces reproductive output in a bumblebee (Bombus impatiens). Journal of Applied Ecology, 61(8), 1932–1943. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14706