By Satsuki Kajiwara

Satsuki is a PhD student in the Entomology Laboratory at Kyushu University, Japan, where she studies ant-associated parasitoid wasps. In this blog post, she shares her discovery of aerial fights between female Ogkosoma cremieri competing for access to ant larvae. Her lastest research in Insectes Sociaux can be read here.

Ant colonies, with their abundant resources and secure environments, are frequently exploited by various organisms that have evolved strategies to infiltrate and persist within them. These organisms, known as myrmecophiles, depend on ants for at least part of their life cycle.

The subfamily Hybrizontinae, which I am currently studying, represents a highly specialized group of parasitoid wasps that attack only ant larvae (Lachaud and Pérez- Lachaud 2012). Their known host ants belong to the genera Lasius (including the subgenera Lasius and Dendrolasius) and Myrmica. Notably, two species in the subgenus Dendrolasius exhibit unusual behavior: they transport their larvae between tree trunks and underground nests depending on the season (Kajiwara and Yamauchi 2023). Because Hybrizontinae wasps parasitize larvae during these transport events, the timing of larval movement is critical for their reproductive success (Komatsu and Konishi 2010).

Females of this subfamily oviposit by inserting their ovipositor into larvae being carried by worker ants—an opportunity that occurs only during the brief moments when larvae are exposed outside the nest.

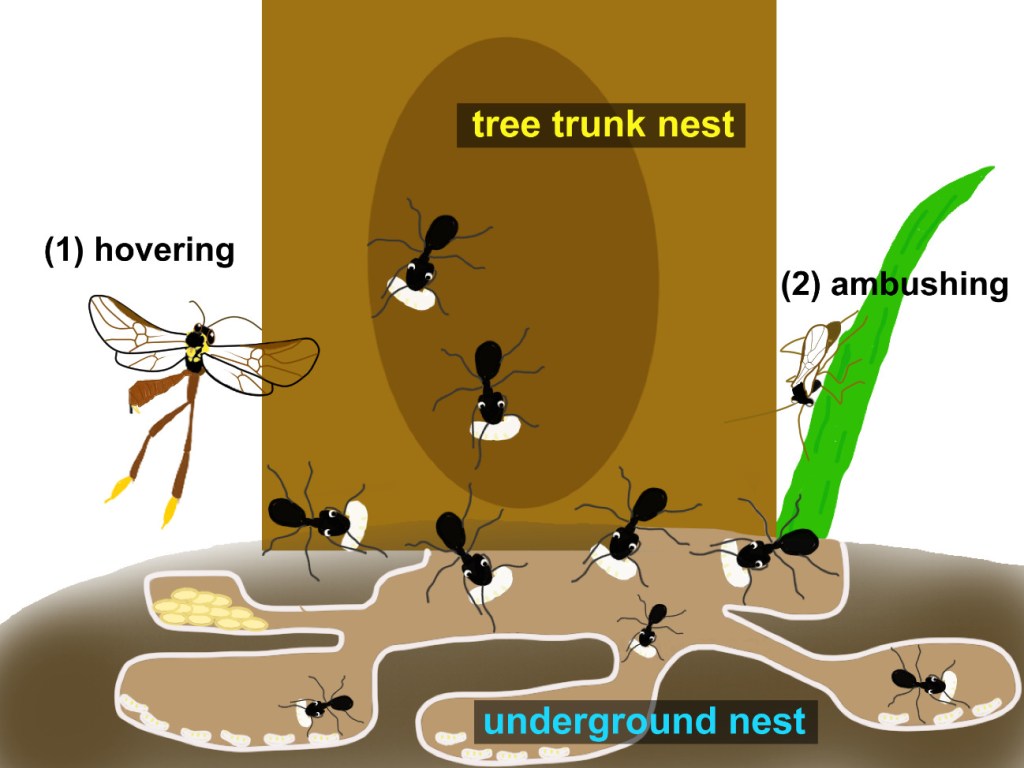

Two basic host-searching strategies are known: (1) hovering near ant nest entrance and (2) ambushing along ant trails by clinging to vegetation.

While surveying ant parasitoid wasps on my university campus in Japan, I was fortunate to discover a hovering female of Ogkosoma cremieri (Romand) near a nest of Lasius capitatus (Kuznetsov-Ugamsky). This unexpected encounter became the starting point for a more detailed behavioral study.

An adult female of Ogkosoma cremieri hovering in front of the nest of Lasius capitatus

Although earlier researchers reported hovering behavior in this species, they did not identify the specific time of day when it occurs. My observations revealed that females hover between 06:30 and 17:00, indicating sustained activity throughout the daytime.

One day I witnessed something remarkable. A female O. cremieri hovered at the nest entrance and approached larvae being carried by workers. When several females were present, they sometimes engaged in aerial jostling: the wasp positioned in front of the nest (red arrow in the image below) drove off an approaching female (yellow arrow) by pushing her while hovering. The displaced wasp was then attacked by ants and dragged into the nest, showing how dangerous it can be for wasps to approach ant brood. Aggressive competition between parasitoid females has been observed before in other ichneumonids, but usually on the ground or on plants — witnessing physical pushing while hovering appears to be a novel behaviour.

Interestingly, L. capitatus workers transport large numbers of larvae from tree trunks into underground nests at night. However, no oviposition behavior by O. cremieri toward these larvae was observed. This pattern suggests that nocturnal larval transport may serve as an adaptive strategy by ants to avoid parasitoid attacks. Consistent with this interpretation, my observations also suggest that O. cremieri is not a nocturnal species. Females became active at night only when the area was illuminated with a flashlight or headlamp—likely a response to artificial light rather than natural nocturnal activity.

Future comparative studies across genera may reveal how morphological traits and behavioral strategies have diversified within this intriguing group of parasitoids.

References:

Kajiwara S, Yamauchi T (2023) Larval transport by adults of Lasius morisitai (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): The season and the time of day. Nat Environ Sci Res 36:15–17 [in Japanese]. https://doi.org/10.32280/nesr.36.0_15

Kajiwara, S., Yamauchi, T. Parasitoidic strategy of Ogkosoma cremieri (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae: Hybrizontinae) against Lasius capitatus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-025-01072-8

Komatsu T, Konishi K (2010) Parasitic behaviors of two ant parasitoid wasps (Ichneumonidae: Hybrizontinae). Sociobiology 56(3):575–584

Lachaud J-P, Pérez-Lachaud G (2012) Diversity of species and behavior of hymenopteran parasitoids of ants: A review. Psyche2012:134746. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/134746