By Peter Chanas

Peter recently completed his Ph.D. at Charles University in Prague. During his doctoral study, he focused on the formation of sunning clusters, the phenomenon in red wood ants as a part of their nest thermoregulation. Currently, he is looking for a research position on ants. Read his latest article in Insectes Sociaux here.

While walking in the European coniferous forest during early spring, some large hills are covered by needles; these are the anthills. If you get closer and look at one of them closely, you will notice a black spot on the nest surface. These are red wood ants, Formica polyctena. They often form huge and dense clusters on the nest surface, in which many ant workers (even queens!) are involved throughout the whole spring.

You may be asking intuitively: Why are they doing this on the nest surface? A long time ago, Zahn (1958) suggested that when ants return to their nest after sun basking, they could transfer heat and thus contribute to the increase in nest temperature. It has been confirmed that sun-basking behavior contributes to the spring nest heating (Chanas and Frouz 2025b). Although the effect on the nest temperature is low, there are other factors which can contribute to the spring nest heating within overall nest thermoregulation. And that is what our research questions were: What factors cause the ants to form clusters on the nest surface? How often do clusters occur?

Sunning clusters, the remarkable phenomenon, occurred in all nests we studied. We were surprised that there was no significant relationship between the occurrence of sunning clusters and nest volume and nest shading, even though such nest properties were shown as crucial in ant nest thermoregulation (see references in our article). Our results suggest that there is a high variation of workers performing sun-basking behavior among individual nests, as similarly shown by Kadochová et al. (2017). It also means that each nest has slightly different microclimatic conditions. Each nest inhabits many ant individuals, which can behave according to it and then ensure optimal temperature conditions in the given nest.

- Why do we call clusters “sunning?” Because when the sun shines, ants form clusters on the nest surface, and the main heat source is the sun, so they form “sunning clusters.” This is their distinctive and conspicuous behavior, and it has attracted the attention of several scientists interested in ant nest thermoregulation.

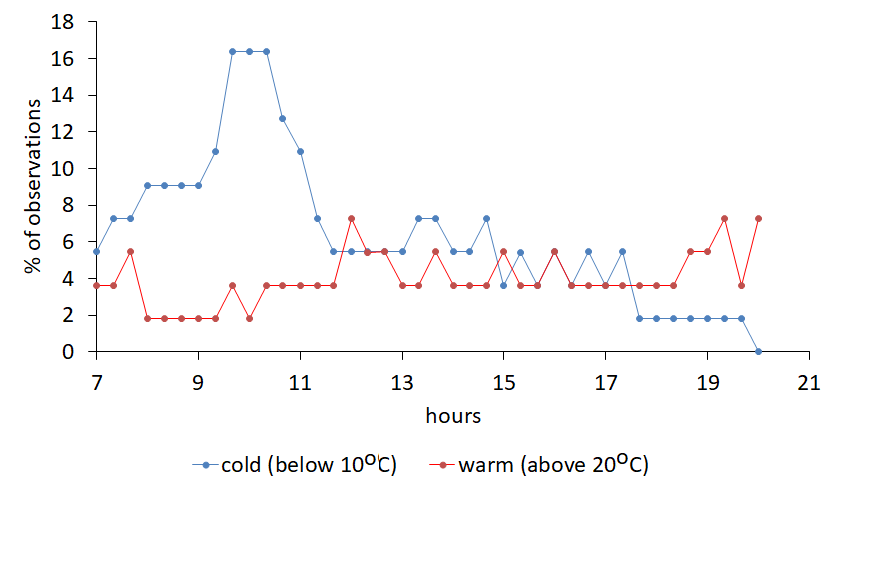

The frequency of clusters strongly depends on the nest temperature and the duration of daylight, unlike the air temperature, which has a lower effect. Thus, at lower nest temperature, ant workers tend to form sunning clusters during warm periods of the day, with a higher outside temperature. At higher nest temperature, clusters are formed during the cold period of the day. We found that the breaking point of the nest temperature where clusters peaked was 4.68°C and of the daylight was 12 h and 40 min. After that, sunning clusters declined very slowly, which you can see only by the statistics. The low nest temperature is very interesting; we expected a different breaking point of nest temperature. Why such a low nest temperature? But sun-basking behavior is just one of several mechanisms within nest thermoregulation. The fact that you do not know something is even more interesting because you can still further ask, think, and feed your curiosity by trying and setting up new experiments and expanding knowledge and contributing to the science and then the whole society to moving on.

Sunning clusters did not completely disappear at the nest temperature above 20ºC, where the opposite was shown by Kadochová et al. (2019). There was rather a gradual decline of clusters. Higher nest temperature accelerates reproduction and is crucial for their proper brood development (Rosengren et al. 1987, Porter 1988). At such high nest temperature, they do not need to further form sunning clusters. Although some workers can still perform sun-basking behavior by their individual need.

If you look at the daily dynamic of occurrence of clusters, you can see that the pattern is different in early spring and different in late spring. Thus, the daily dynamic changed significantly in early and late spring (Fig. 2). In early spring, when the nest temperature is low, sunning clusters peaked in late morning and then decreased. In late spring, however, we found that once a nest heated up, the clusters became much less frequent and occurred without a clear diurnal pattern but in obvious association with colder weather.

We had a huge dataset. A large dataset was generated, including nineteen cameras (Fig. 3). By using the cameras, we were able to notice something that the ordinary eye would not notice in the field. When you have “more eyes” looking at something, you are more likely to notice things you had not considered—because the mind tends to only see what it is prepared to see. In this case, we noticed clusters in association with colder weather that occurred sometime even in late spring. Such clusters we called “non-sunning clusters” (Fig. 4). This was a surprising finding, prompting the question: Why do they occur there under a cloudy sky or in cold weather for most of the day in early spring—and sometimes even during brief periods in late spring? These clusters likely have no significant effect on the regulation of nest temperature. But it can bring new insight into the organisation of ant colonies, but it needs further investigation. Currently, we are working on further findings based on another dataset that will expand our knowledge of ant nest thermoregulation.

Since ants are ectothermic animals, the formation of clusters can be quite “mechanical”. Due to their reaction to change the nest temperature and environmental conditions. A simple and plausible algorithm for cluster formation could be based on environmental conditions and social cues: in cold weather and in the presence of other workers on the nest surface, individuals tend to cluster together. When the nest surface is cold, they seek sunlight when available; when it becomes hot, they move into shaded areas to avoid overheating (Kadochová et al. 2019). Similar to how people enjoy basking in the sun during early spring but more avoid it during the peak of summer, red wood ants adjust their behavior based on nest and air temperature. However, unlike humans, they form clusters—an adaptive strategy that reduces their surface-to-volume ratio, helping to minimize heat loss compared to individual ant workers.

In conclusion, red wood ants tend to form clusters on the nest surface in early spring when nest temperatures are low or when workers are exposed to cold conditions. This behavior likely persists into late spring during chilly mornings, evenings, or periods of cold weather. In essence, the formation of sunning clusters is closely tied to nest temperature, air temperature, and daylight availability. Red wood ants appear to integrate cues from both inside the nest (internal temperature) and the external environment (sunlight or cold) to decide whether or not to form sunning clusters on the nest surface.

References

Chanas P., Frouz J. 2025b. Sunning clusters of ants contribute significantly, but weakly to spring heating in the nests of the red wood ants, Formica polyctena. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 15: 28–33. https://doi.org/10.14712/23361964.2025.4

Kadochová Š., Frouz J., Roces F. 2017. Sun basking in red wood ants Formica polyctena (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): Individual behaviour and temperature-dependent respiration rates. PLoS ONE 12(1): e0170570. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170570

Kadochová Š., Frouz J., Tószögyová A. 2019. Factors influencing sun basking in red wood ants (Formica polyctena): a field experiment on clustering and phototaxis. J. Insect Behav. 32: 164–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10905-019-09713-0

Rosengren R., Fortelius W., Lindström K., Luther A. 1987. Phenology and causation of nest heating and thermoregulation in red wood ants of the Formica rufa group studied in coniferous forest habitats in southern Finland. Ann. Zool. Fennici 24: 147–155.

Porter S.D. 1988. Impact of temperature on colony growth and developmental rates of the ant, Solenopsis invicta. Journal of Insect Physiology 34: 1127–1133. https://doi.org10.1016/0022-1910(88)90215-6

Zahn M. 1958. Temperatursinn, Wärmehaushalt und Bauweise der Roten Waldameisen (Formica rufa L.). Zoologische Beiträge 3: 127–194.